GEM Distribution

In one of the introductory lectures on machine learning (a long time ago) I learnt some basics about mixture models, EM algorithm; the standard stuff. I was always curious about learning the nitty-gritty of the workings and the underlying concepts. Finally, (after many years!) I had the time to dig in a bit deep. Specifically, I focused my energies on the Bayesian nonparameteric models. This series of posts is an attempt to document the most important learnings.

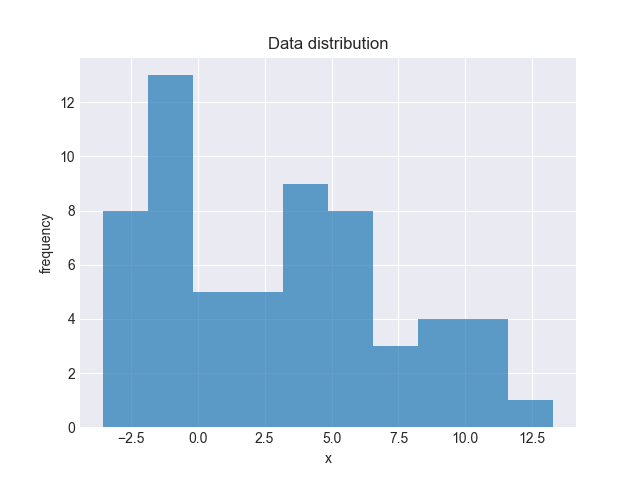

Let me start with some motivation. Suppose you have 1-dimensional data as above. Your task is to infer the underlying data generation process. How would you go about doing it? Perhaps, you would design a mixture model comprising of 2-3 Gaussian distributions. But what if your data is high dimensional and you cannot guess apriori how many components you need. Or perhaps you want to design a module that takes as input any such arbitrary data and outputs a reasonable mixture model that explains the data. This is where you will need to use Bayesian nonparametric models. Unlike finite mixture models, when you fit data to these models, you also learn the number of distribution components underlying the data. Have I piqued your interest yet?

Beta Distribution

Let’s start by building some basics. What is Beta distribution? Mathematically,

\[P(x| \alpha, \beta) ~=~ \frac{\Gamma(\alpha + \beta)}{\Gamma(\alpha) \cdot \Gamma(\beta)} \cdot x^{\alpha-1} \cdot (1-x)^{\beta -1}\]Intuitively, we can think of Beta distribution as a distribution over Bernoulli distributions. For example, suppose you have results of $n$ coin tosses from a biased coin and you want to compute the posterior distribution of the bias of the coin. You could do that using the Bayes’ formula and with the Beta distribution as prior with appropriate parameters (something that captures your prior information). One of the amazing properties of the Beta distribution (and something we shall use later) is that it is a conjugate prior of the (2-outcome) categorical distribution, like the biased coin in our example. What that means is that the posterior will also be a Beta distribution with easily derivable parameters. (If you are wondering why this is a big deal, for most natural problems, it is difficult to compute a closed form expression of the posterior distribution. In the case of the coin toss example above, we get the exact form of the posterior distribution almost for free with the Beta prior).

In case you are new to the concept of Beta distribution, I suggest you read up on it, for example, here.

Dirichlet Distribution

A Dirichlet distribution is simply an extension of Beta distribution to $K$ dimensions. Instead of the coin toss example, think of biased dice rolls. Analogous to the Beta distribution which had 2 parameters, the Dirichlet distribution is defined by $K$ parameters (which can be thought of as the weights for the $K$ outcomes). Note that a draw from this distribution is a vector in K-1 dimensional simplex.

\((c_1, c_2, \cdots c_K) ~\sim~ Dir\left(\alpha_1, \alpha_2, \cdots \alpha_K \right)\), where $\sum_i c_i = 1$.

I’d highly recommend watching this video for a better understanding of Beta and Dirichlet distributions. For the purposes of this post, we care about just two very interesting properties of Dirichlet distribution.

- Marginal distribution of $c_i$ follows Beta distribution, i.e. \(c_i ~\sim~ Beta\left( \alpha_i, \sum_{j \neq i}\alpha_j \right)\) Can you try proving this? solution

- Neutrality property: Let $c_{-i}$ denote the vector obtained by removing $c_i$ from $ (c_1, c_2, \cdots c_K)$. Then $c_i$ is independent of $\frac{c_{-i}}{1 - c_i}$ and \(\frac{c_{-i}}{1 - c_i} ~\sim~ Dir\left(\alpha_1, \cdots \alpha_{i-1}, \alpha_{i+1} \cdots \alpha_K \right)\) Proof

Sampling from Dirichlet Distribution - Stick-breaking Approach

Suppose we want to sample from the distribution $Dir\left(\alpha_1, \alpha_2, \alpha_3, \alpha_4 \right)$. In order to do so, we shall successively apply properties mentioned above. Let the actual sample be denoted by $ (c_1, c_2, c_3, c_4)$.

We can draw the first sample as:

\[u_1 ~\sim~ Beta(\alpha_1, \alpha_2+\alpha_3+\alpha_4)\]By property 2, since $u_1$ and $(1-u_1)\cdot Dir(\alpha_2, \alpha_3, \alpha_4)$ are independent, we can set $c_1 = u_1$ and sample $u_2$ as:

\[u_2 ~\sim~ Beta(\alpha_2, \alpha_3+\alpha_4)\]and set $c_2 = (1-u_1) \cdot u_2$. Similarly,

\[u_3 ~\sim~ Beta(\alpha_3, \alpha_4)\]and $c_3 = (1-u_1) \cdot (1-u_2) u_3$. Finally, $c_4 = 1 - (c_1 + c_2 + c_3)$.

Personally, I find it quite amazing that we can draw samples from a seemingly complicated distribution by recursively using a much simpler Beta distribution. Now, the even more interesting aspect of this procedure is that, if we had access to an infinite number of parameters $ (\alpha_1, \alpha_2, \cdots)$ we could have run the procedure indefinitely, i.e.

\[c_1, c_2, \cdots ~\sim~ Dir\left(\alpha_1, \alpha_2, \cdots \right)\]From a computational perspective of course, we would truncate the process after $N$ rounds of recursion, but even then to generate samples from this distribution you have to specify all of the parameters. This is aside from the fact that it would be a nightmare to understand the resulting distribution.

There does exist one very simple but elegant workaround. Each of the $u_i$ (see example above) can be drawn from the same Beta distribution, namely, $Beta(1, \alpha)$, where $\alpha > 0$. Let’s pause here for a moment. How does $Beta(1, \alpha)$ behave? For $ p ~\sim~ Beta(a, b)$, we know (or at least we should know!)

\[\mathbb{E}[p] ~=~ \frac{a}{a+b}\]i.e. $\alpha$ decides how big the first part of the stick is relative to it’s length. This means, for large values of alpha, we pick smaller size sticks in the beginning. On the other hand, if $\alpha$ is small, we would pick bigger chunks in the beginning (on expectation). This property will come in very handy when we use this for inference of cluster assignment.

So, what do we have. Infinite iid draws from $Beta(1, \alpha)$:

\[u_1, u_2, \cdots ~\sim~ Beta\left(1, \alpha \right)\]used to compute the actual vector using the stick breaking approach from above. $\mathbf{c} = (c_1 = u_1, c_2 = (1-u_1)u_2, \cdots )$. The distribution so obtained is the $GEM(\alpha)$ distribution, where $\alpha$ is called the concentration parameter.

Oh, I almost forgot. GEM distribution after three mathematicians, Griffith, Engen and McCloskey. If you’d like to see GEM distribution in action, you can find some toy code here and here. In the next post, I will talk about the Chinese restaurant process and how to use it for inference.